This shift of perspectives is also given to the game’s factions, in keeping with Japanese role-playing tradition.

Pleasingly, Evoland 2 makes the most of its time-travelling plotline, offering Chrono Trigger-esque viewpoints where key events are either foreshadowed or ruminated long after their occurrence. This time out, Evoland 2’s aesthetics are used to signal three different ages: an ancient eight-bit era, a contemporary world built from SNES bitmaps, and a Dreamcast-looking future. Naturally, that opens a Pandora’s Box of complications. His rescuer, an energetic girl named Fina, offers care for the wounded warrior, and when Kuro regains consciousness, the duo attempt to learn more about the hero’s past. Despite the significance of the situation, our protagonist, a red-haired, good natured, young man named Kuro is found in a forest, with little remembrance of both the event and his identity. The context is a time of perceived optimism, following a grueling war between demons and humans, with the latter faction having shouldered sacrifice and risk to develop a technology that would overwhelm the opposition.

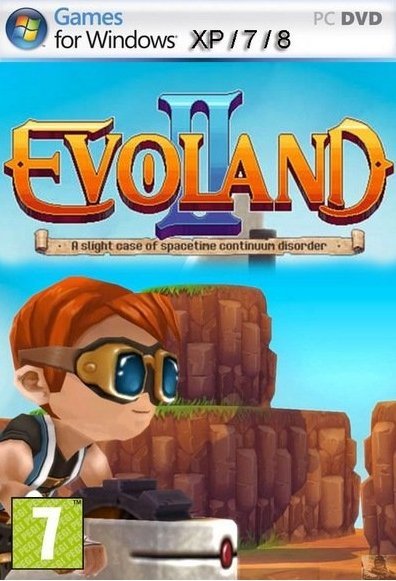

While Evoland 2’s introduction mimics the evolutionary elements that propelled its predecessor into popularity, soon after exposition emerges. But more importantly, the follow-up’s narrative seems culled from the golden-age of JRPGs, with characters and a storyline that flawlessly imitate a collection of role-playing classics. From The Legend of Zelda, Super Mario Bros., Final Fantasy, Street Fighter II, Bomberman, to Diner Dash, Evoland 2 offers a steady stream of homage- as the game catalogs a list of gaming’s noteworthy play mechanics. Like any component sequel, the achievements of its predecessor are augmented, with the title providing a persistent procession of allusions and reproductions of classic gaming experiences. Wisely, that offense is corrected by Evoland 2: A Slight Case of Spacetime Continuum Disorder. While the concept was innovative enough for its predecessor to win the Ludum Dare competition, ultimately Evoland’s expedition wasn’t as engaging as its inspirational material, with the game advancing only a skeletal storyline. As players persevered, new elements were added to the game, making the journey mirror a chronological progression that started with the Gameboy and concluded with the 16-bit generation. But for every success like Spelunky, SteamWorld Dig, or TowerFall, there are titles that aren’t as subtle, supplying little more than a disjointed hodgepodge of references to gaming’s past.Įvoland, a 2013 release from Bordeaux-based Shiro Games was guilty of this transgression. For indie developers, there’s a similar effort to tap into sentimentality, with a procession of new games that mimic the mechanics or pixelated graphics of previous eras. Relentlessly, publishers attempt to reinvigorate salient gaming memories, with a cavalcade of remakes, reboots, and remasters vying for our disposable income. Nostalgia is a tragically fragile sentiment.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)